Going by economic news in the recent fortnight economic data suggests positive results in China and Western Europe. Going by the stock markets, even Bursa Malaysia, investors are regaining a sustained confidence that the worst is over.

But, then, if we go by that great contrarian, Nouriel Roubini, what we are seeing is the be upward climb of what he expects to be a "double-dip" recovery or a "W". In a sense, he's in good company with many economists. The caution given by Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao is also consistent with this line of sentiment.

Reasons for the "false dawn" caution

Almost every government in the world has, in the course of 2008-2009, implemented stimulus packages. Every government budget is in deficit. Now deficit spending in and, of itself, is not unusual since the conventional Keynesian wisdom is that if the private sector is hesitant, the government puts in investments so that an economy will equilibrate at a higher level than before. This is called economic growth.

Stimulus spending is quite different from the garden-variety deficit spending. A stimulus requires excessive investment that is designed to prevent an economic contraction.

To finance this type of deficit-stimulus spending, governments the world over have created large amounts of sovereign debt. These are Treasury bills, government bonds or, whatever they are called. It means that the government is borrowing money to spend. The idea is to spend so much money that the nervous citizens become convinced that they need no longer be nervous and, they should start spending again with great aplomb and confidence. This is called consumption.

Now, let's take a look at the Chinese economy in this context.

Many economies, including Malaysia, are looking to China as a panacea that may reduce significantly or, remove completely, the global economic malaise.

Private consumption is running at about 36 percent of GDP in China right now. That is half of the US consumption rate, and it’s about two-thirds of the consumption rate of Europe.

Bolstered by a $586 billion government stimulus program and a surge in lending by state-owned banks, many expect China to be the first major economy to bounce back from the global recession.

But, many economists realise that the composition of China’s growth remains unbalanced. Aggressive increases in government spending and investment by state-owned enterprises has cushioned the impact of weak exports. But the increased government spending have not been matched by comparable increases in private consumption.

It is a fact that spending by Chinese households as a percentage of GDP is only half the US consumption ratio and remains significantly below private spending levels in Europe and Japan. Worse still, despite rising sales of items such as automobiles and household appliances, the ratio of private spending to GDP in China today has actually fallen relative to Chinese spending levels of a decade ago. Clearly the Chinese households are being very guarded.

Social safety nets and consumption

China has some similarities with Malaysia in that both countries have relied on the so-called investment-export model of economic planning.

The other similarity may be the absence of significant social safety nets.

China doesn’t have a complete social-security system. As at 2007, only one-third of the urban population was covered by the social-security system. And for rural residents, most of them don’t have social security. And also in past years, the cost for education, for medication, for housing has increased quite rapidly—much more rapidly than GDP growth and income growth. The same may also be said of Malaysia.

One of the main obstacle to boosting private consumption in China is to persuade a large generation of Chinese workers and families who have been displaced under the guise of state-owned enterprise reform—who have lost the sort of cradle-to-grave support, the so-called iron rice bowl, the safety net that had been in place in the prior state-owned enterprise regime—to convince them that it’s okay to begin to draw down the excesses of precautionary saving.

Income-gap and consumption

Some economists have observed that income distribution has a significant impact on consumption and, that, therefore, the Chinese government needs to make some adjustments to reallocate income distribution—how much goes to citizens, how much to governments, and how much to enterprises. This is a macroeconomic adjustment that can be achieved with new fiscal policies, including changes in tax policy.

In Malaysia's case, income disparity is also widening. This means that the tax-base remains narrow which has an impact on the government's ability to fund its budget deficit.

Social safety net financing and impact on consumption

Increased spending on social security may not necessarily lead to increased private consumption. The key issue may be how social security is financed. This goes back to the matter of deficit spending.

A case in point is the rural health insurance in China, which is subsidized by the government. The presence of this type of subsidy prevents the phenomenon of crowding out. The rural Chinese are not required to spend a lot to purchase health insurance. This created enough disposable income such that consumption increased.

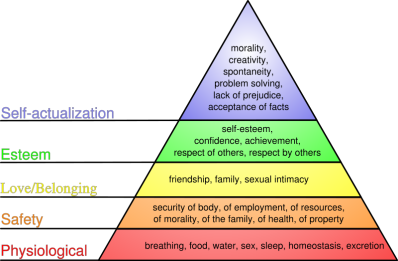

The bottom line is, if people feel that there is a social safety net, they will have greater confidence to apply their disposable income to consumption. Otherwise, the instinct is to save.

And, we do have to wonder whether this use of the Keynesian paradigm to examine economic issues is still valid? It probably is, but, we will do well to constantly ask this question albeit at a philosophical level. See my posts on conspicuous consumption.

The reason for the issue of consumption to be raised is that consumption is one of the elements of the Keynesian economic model. In the desire to equilibrate, many economic thinkers and planners are looking to boost the "C" component to match the "G" and "I". For a recap on this last bit, please check the post I made earlier, Stimulating the G-spot.

.

. .

. .

.